1. The Mayo Clinic, PTSD, symptoms and causes. Accessed February 14, 2024. www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/post-traumatic-stress-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20355967c

2. VA National Center for PTSD. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_adults.asp

3. Goldstein RB et al. The epidemiology of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016; 51(8):1137–1148.

4. Lehavot K, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder by gender and veteran status. Am J Prev Med. 2018 Jan;54(1):e1-e9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.09.008

5. Kessler RC, Rose S, Koenen KC, et al. How well can post-traumatic stress disorder be predicted from pre-trauma risk factors? An exploratory study in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. World Psychiatry. 2014 Oct;13(3):265-74. doi: 10.1002/wps.20150

6. Davis LL. The economic burden of posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States from a societal perspective. J Clin Psychiatry. 2022 Apr 25;83(3):21m14116. doi: 10.4088/JCP.21m14116

7. Bryant RA. Post-traumatic stress disorder: a state-of-the-art review of evidence and challenges. World Psychiatry. 2019;18(3):259–269.

8. Rosellini AJ et al. Recovery from DSM-IV post-traumatic stress disorder in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Psychol Med. 2018 Feb;48(3):437-450. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717001817

9. Lin CC, Liu YP. Pharmacological implications of adjusting abnormal fear memory: Towards the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022;15(7):788. doi:10.3390/ph15070788

10. Clancy KJ, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder is associated with α dysrhythmia across the visual cortex and the default mode network eNeuro. 2020;7(4):ENEURO.0053-20.2020. doi:10.1523/ENEURO.0053-20.2020

11. Akiki TJ, et al. Default mode network abnormalities in posttraumatic stress disorder: A novel network-restricted topology approach. Neuroimage. 2018;176:489-498. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.05.005

12. Miller DR, et al. Default mode network subsystems are differentially disrupted in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2017;2(4):363-371. doi:10.1016/j.bpsc.2016.12.006

13. Sripada RK, et al. Neural dysregulation in posttraumatic stress disorder: Evidence for disrupted equilibrium between salience and default mode brain networks. Psychosom Med. 2012;74(9):904-911. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e318273bf33

14. Szeszko PR, Yehuda R. Magnetic resonance imaging predictors of psychotherapy treatment response in post-traumatic stress disorder: A role for the salience network. Psychiatry Res. 2019;277:52-57. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.005

15. Selemon LD et al. Frontal lobe circuitry in posttraumatic stress disorder. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks). 2019;3. doi:10.1177/2470547019850166

16. Morris MC, et al. Cortisol, heart rate, and blood pressure as early markers of PTSD risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;49:79-91. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2016.09.001

17. Dunlop BW, Wong A. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in PTSD: Pathophysiology and treatment interventions. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;89:361-379. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.10.010

18. Katrinli S, et al. The role of the immune system in posttraumatic stress disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12(1):313. doi:10.1038/s41398-022-02094-7

19. Carmassi C, et al. Decreased plasma oxytocin levels in patients with PTSD. Front Psychol. 2021;12:612338. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.612338

20. Schein J et al. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States: a systematic literature review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021 Dec;37(12):2151-2161. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2021.1978417

21. Kantor V et al. Perceived barriers and facilitators of mental health service utilization in adult trauma survivors: A systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017 Mar;52:52-68. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.12.001

22. Grinage B.D. Diagnosis and management of post-traumatic stress disorder. Am Fam Physician. (2003);68(12):2401-2409. PMID: 14705759.

23. Rojas SM et al. Understanding PTSD comorbidity and suicidal behavior: associations among histories of alcohol dependence, major depressive disorder, and suicidal ideation and attempts. J Anxiety Disord. 2014 Apr;28(3):318-25. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.02.004

24. Edmondson D, von Känel R. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular disease. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017 Apr;4(4):320-329. doi: 10.1016/S2215‑0366(16)30377‑7

25. Krantz DS, Shank LM, Goodie JL. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a systemic disorder: Pathways to cardiovascular disease. Health Psychol. 2022 Oct;41(10):651-662. doi: 10.1037/hea0001127

26. Boscarino JA. Posttraumatic stress disorder and mortality among U.S. Army veterans 30 years after military service. Ann Epidemiol. 2006 Apr;16(4):248-56. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.03.009

27. Nichter B, Norman S, Haller M, Pietrzak RH. Physical health burden of PTSD, depression, and their comorbidity in the U.S. veteran population: Morbidity, functioning, and disability. J Psychosom Res. 2019 Sep;124:109744. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109744

28. Davis LL. The economic burden of posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States from a societal perspective. J Clin Psychiatry. (2022) Apr 25;83(3):21m14116. doi: 10.4088/JCP.21m14116

29. The Mayo Clinic, PTSD, Diagnosis & Treatment Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – Diagnosis and treatment – Mayo Clinic. Accessed January 17, 2024.

30. American Psychological Association. Clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of PTSD. Accessed February 5, 2024. Medications (apa.org)

31. Watkins LE, Sprang KR, Rothbaum BO. Treating PTSD: A review of evidence-based psychotherapy interventions. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018 Nov 2;12:258. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00258

32. Cusack K, et al. Psychological treatments for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016 Feb;43:128-41. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.10.003

33. Bonfils, KA et al. Functional outcomes from psychotherapy for people with posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2022 Jun;89:102576. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102576

34. Lewis, C., Roberts, N. P., Gibson, S., & Bisson, J. I.. Dropout from psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2020 Mar 9;11(1):1709709. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1709709

35. Steenkamp, M. M., Litz, B. T., Hoge, C. W., & Marmar, C. R. Psychotherapy for military-related PTSD. JAMA. 2015 Aug 4;314(5):489-500. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.8370

36. Gagnon-Sanschagrin P et al. Identifying individuals with undiagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder in a large United States civilian population – a machine learning approach. BMC Psychiatry. 2022 Sep 29;22(1):630. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04267-6

37. Bryant RA. Post-traumatic stress disorder: a state-of-the-art review of evidence and challenges. World Psychiatry. 2019;18(3):259–269. doi: 10.1002/wps.20656

38. Stein MB, Rothbaum BO. 175 Years of progress in PTSD therapeutics: Learning from the past. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Jun 1;175(6):508-516. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17080955

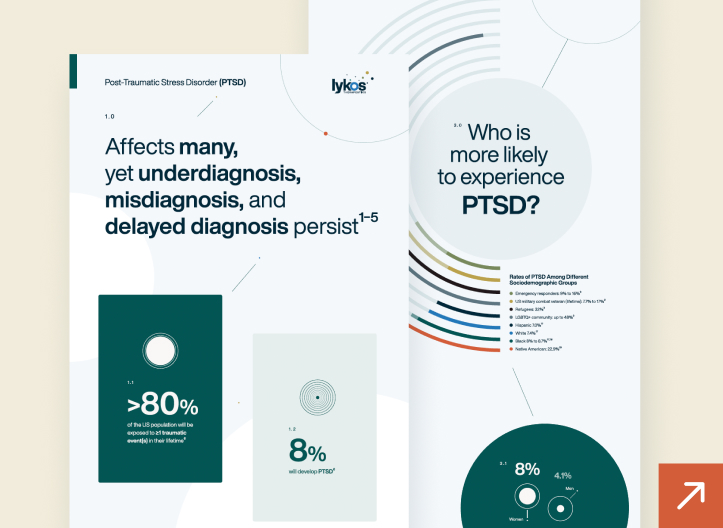

Prevalence & symptoms

PTSD is a serious mental health condition that can develop when a person experiences or witnesses a traumatic event.1 PTSD affects approximately 13 million Americans each year2 with women and disadvantaged or marginalized groups more likely to be affected.3 The prevalence of PTSD is higher in military personnel than in the general population.4 However, it may not be as widely known that the most frequent cause of PTSD is non-combat-related trauma (e.g., sexual violence, unexpected death of a loved one, life-threatening traumatic event or interpersonal violence).5

PTSD results in debilitating symptoms including nightmares and intrusive thoughts related to the trauma, mental and/or physical distress in response to trauma-related stimuli, avoidant behaviors, negative thoughts and feelings, and hyperarousal.6,7 These symptoms can impact nearly all aspects of a person’s life including interpersonal relationships, work and daily activities.1 PTSD can also be a chronic condition with a World Health Organization study showing that after ten years post-trauma, nearly a quarter of people had not recovered.8